Authored by Edgar O. Najera

In the natural world, the power of nature has programmed bees to constantly pursue a means of production; such behavior has made them one of the most important organisms in Earth’s ecosystems for without their labor and their need to follow their instincts, we would not have the flowers and plants in the ecological world. It is so important and crucial for our fauna to grow and reproduce. This natural harmony has become one of the most important natural processes on our planet and it is also a system where nature rewards bees with honey produced by the drones working by the thousands. Evolution is one of the most powerful forces in the universe and has allowed bees to find a way to survive and reproduce by amassing storehouses of honey so they can survive through the wintertime. This pattern of behavior is one that humans share with bees when it comes to hoarding properties and goods. Human labor, through the modern work market, is essentially transformed into credit that works as currency (imaginary or physical objects of meaning) which humans can spend and exchange for any type of good. That credit then gets introduced to a web of transactions and circulation in the economic machine. However, unlike bees, who have been programmed by thousands of years of evolution to adapt a cyclical behavior, humans have developed a means of production that corrupts the planet as well. According to American environmentalist Annie Leonard, proponent and champion of criticism on excessive consumerism, people spend the majority of their time watching TV and this leads to a cycle where people want to spend more money. This cycle is known as the “Material’s Economy Cycle” and that system is responsible for the increase in human unhappiness and the trashing of the planet.

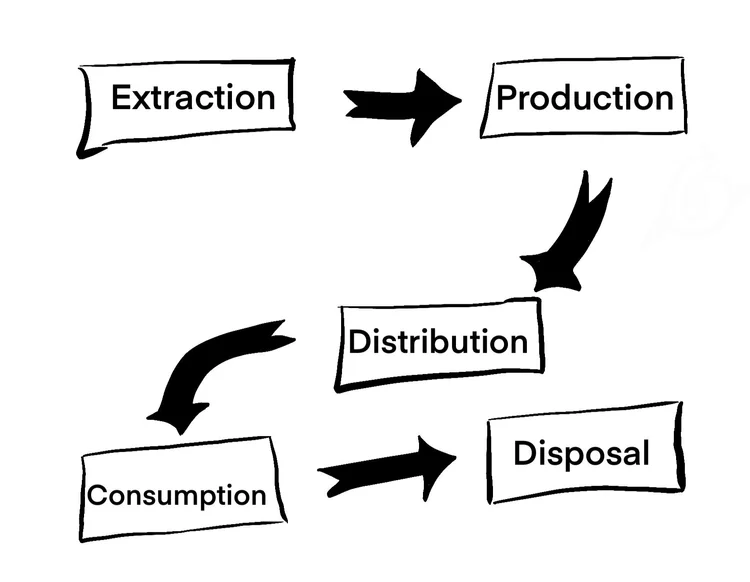

The task for us now is to break down this system and understand if there is any opening for us to regain a little bit of control in our spending habits. Annie Leonard spent 10 years traveling around the world and putting together powerful research on sustainability and ecological awareness. She wanted to find out how stuff is made and sold in the market and what eventually happens to all the stuff. In her film, The Story of Stuff, Leonard explains that due to the linear processes of the production of stuff, the world is in crisis because you cannot run an indefinite system on a finite planet. This system, according to Leonard, “interacts with societies, cultures, economies and the environment.” People live and work all along the stages of this system which moves from extraction to production to distribution to consumption, and finally, to disposal. Both the U.S. government and American corporations regulate and control this system to ensure the economy does not flounder. This aforementioned system is structured in a way that is both detrimental to people and the world. Let us break it down. Leonard explains that extraction is the process by which humans exploit the natural resources of the world in “trashing the planet, blowing up mountains to get the metals inside, using up all the water and wiping out the animals. In the past three decades, one-third of the planet’s natural resources have been consumed. People usually need work and are also drawn by this consumer culture” (Louis Fox, 2007). And what happens to the people that live in the areas that get destroyed? Well, they move to more industrialized places and become drones to the very consumer’s economy that took away their resources. “Globally 200,000 people a day are moving from environments that have sustained them for generations into cities, many to live in slums working day by day no matter how toxic that may be for them” (Louis Fox, 2007). The communities that get the most affected by this rape of the natural world are the people that not only lack knowledge but also the resources to fight for what belongs to them. The reason why it is so easy for corporations to seize the raw materials is that, according to them, “the people that live in the lands they exploit[,] do not own or deserve the resources of the land even though they have been living there their whole lives—they don’t own the means of production and they are not buying a lot of stuff. In this system, the people who do not buy a lot of stuff don’t have value” (Louis Fox, 207). After extracting the materials, those materials move to production. What happens in the factory is something pretty scary in terms of people’s general health. Energy is usually used for production which produces in turn a byproduct of, “toxic chemicals with the natural resources [which result in] contaminated products” (Louis Fox, 2007). Leonard discovered too in the making of this film that, “there are over 100,000 synthetic chemicals in use in commerce today. None of those products have been tested for health purposes or for synthetic health impact, that means they interact with all the other chemicals we are exposed to every day–we do not know the full impact on health and the environment of all these toxic chemicals” (Louis Fox, 2007). Factory workers, who are mostly women, and in third world countries children, are the ones who suffer the most. “A lot of these toxins leave the factories in products, but even more leave as byproducts or pollution. In the U.S., our industry admits to releasing over 4 billion pounds of toxic chemicals a year” (Louis Fox, 2007). So as we can see, this monster machine consumes and eats not only the raw materials of the earth but consumes people’s energies and health as well. We bring all those mysterious chemicals to our homes in electronics and other purchases. “So besides the raw materials, people’s health is also wasted in this industrial system. Whole communities wasted” (Louis Fox, 2007). Next step in this material economy is Distribution. Once the raw materials have been transformed into goods, “they are moved into the process of “Distribution.” The goal in the distribution stage is to keep prices down, keep the people buying, and keep the inventory moving (Louis Fox, 2007). What is actually interesting here is that products are usually cheap, Leonard says. If you go to your local dollar store you will find products that have already been manufactured and you can get a bunch of stuff for a lower price. Leonard says that the reason why prices are low is that the workers and the planet have already paid the high price. Corporations “don’t pay the store workers very much and they skimp on health insurance every time they can. It’s all about externalizing the costs-–we aren’t really paying for the stuff we buy” (Louis Fox, 2007). And “[children] in the Congo paid with their future—30% of the kids in parts of the Congo now have had to drop out of school to mine coltan—a metal we need for our disposable electronics” (Louis Fox, 2007). These are people at a high disadvantage since they usually have to “cover their own health insurance. And none of these contributions are recorded in any accounts book. That is the company owners externalize the true costs of production. (Louis Fox, 2007). The people that end up paying the price for the product we enjoy so much like our smartphones and our light shiny computers are people in other places that need work to survive. We are the consumers, we are responsible for this system as well just as bees are responsible for the amassing and consumption of nectar. This leads us to the “Golden Arrow of Consumption.”

The Golden Arrow of Economy and the Human Treadmill

“Golden Arrow of Consumption.” Leonard says that the golden arrow is the heart of the system and the engine that drives it. “Making sure that this arrow is always running in the main jobs of the government and cooperation at all costs. We have become a nation of consumers” (Louis Fox, 2007). One of the most terrifying things about this system is that Leonard thinks that, “our primary destiny has become that of consumers, not mothers, farmers, but consumers” (Louis Fox, 2007). This is not just trivial, Leonard has done her research and it has revealed so much. An important aspect of our social lives and how much we are worth in this consumer world is precisely how much we contribute to this “arrow of consumption”. The less you consume, the more it reveals that you do not possess the means (money) to delight and indulge in the “goods” the country has to offer, the less you are a conduit for transactions and therefore the less you contribute to the nation. “It is precisely our shopping that keeps this arrow going and what keeps the materials flowing from extraction to production to distribution and finally to the dumps” (Louis Fox, 2007). But why is it so hard for people to stop shopping, and to understand the fact that our human activity is harming our home? Well, Leonard believes that there are two subtle yet powerful forces at play that essentially control our wants and manipulate our desires—Plan Obsolescence and Perceived Obsolescence. We will return to these concepts in a bit. First, one has to consider other forces as well such as media marketers and data analysts. Essentially, these people use consumer data to know exactly what consumers want. This strategy is constructed by surveillance trends and consumer patterns that reveal what people are buying during specific times and then targeting them through ads in their media feeds. With Planned Obsolescence producers essentially accomplish a never-ending loop with consumers buying whatever specific product. The best example of this is Apple Inc. essentially Apple has accomplished such a mass monopoly on smart devices that has transformed life into a futuristic utopia where all products are color coordinated and connected to one another. Given that at some point, Apple’s goal is to sell as many products as possible and produce the revenue for the company to keep manufacturing Apple products, eventually, everyone will own an iPhone with their respective gadgets. However, if you notice with every iteration of smartphones, something minuscule, almost unnoticeable, changes in the phone: either the charger, the camera, or even the shape of the lighting port (the part where the charger goes). This way producers ensure that consumers will not only want the new phone but jettison all the chargers and the headphones since they don’t match their respective devices anymore. In this fashion, Apple keeps updating its iPhone owners to dump their once upon a time brilliant phones for the new shiny one resulting in a never-ending cycle of constant phone updates. All of the old stuff goes out to the trash. Planned obsolescence, Leonard says, is another word for “planned for the dump”. But we also have Perceived Obsolescence which is mostly self-reinforced through social dynamics of wealth display. Perceived obsolescence “convinces us to throw away stuff that is still perfectly useful. How do they do that? Well, they change the way the stuff looks, so if you bought your stuff a couple of years ago, everyone can tell that you haven’t contributed to this arrow recently and since the way we demonstrate our value is by contributing to this arrow, it can be embarrassing” (Louis Fox, 2007). I experienced this issue once when I was at a Walmart with several of my summer camp friends. I owned a phone that had been passed down to me by a good friend who had updated her phone. I saw this as a great way to save money and at the same time own the famous iPhone. I was happy with the phone and it worked perfectly fine. The issue was that it was actually an iPhone 4 and by that time the upgrades had been rolling out like coins from a casino machine. My friends of course made fun of my phone and I was embarrassed. Suddenly I started to make sure that people around me wouldn’t notice the type of phone I had. The pressure from people around me was difficult and so of course I eventually gave in and updated my phone. People do this unconsciously, however, and we usually don’t realize we do this to one another since the steps of consumption exist in our intersubjective space in the same way we agree about the marvelous status of the Ferrari brand or the arbitrary worth of a 100 dollar bill–It’s a social contract. Leonard explains that Fashion is a prime example. She asks, “Have you ever wondered why women’s shoe heels go from fat one year to skinny the next to fat to skinny? It is not because there is some debate about which heel structure is the most healthy for women’s feet. It’s because wearing fat heels in a skinny heel year shows everyone that you haven’t contributed to that arrow recently so you’re not as valuable as that skinny heeled person next to you or, more likely, in some ad” (Louis Fox, 2007). This ensures we keep on buying shoes. The media that we all consume generally leads us to want specific products to be accepted into a society since ultimately we all play the game collectively and usually follow the crowd. This social phenomenon is known as Social Proof coined by Robert Cialdini in his 1984 book Influence: The Psychology of persuasion. Basically, humans value and pursue a specific behavior, or value a specific thing, based on the approval of others around us. What makes a specific product have value depends on the number of people who value said product. In essence, this is basically what many call following the herd. We do not like to stand out as outliers because that just means we fall outside the norm and it requires more work to think for ourselves and design our own value. Consequently, we refer to the opinions of the whole to define social values and ethics-–if everyone is buying an iPhone then it means that the iPhone has metaphysical value beyond being a simple multipurpose physical apparatus. The operations of marketers and data analysts coupled with the tactics of Planned Obsolescence and Perceived Obsolescence leave people with no defenses against such psychological manipulation.

What makes such marketing even more powerful is how much it has been harnessed and plugged into the screen in every corner of our homes and not only our homes but our bodies. In quotidian life, it is not enough now to have a flat-screen mounted on the wall, we have to have our computer equipped with an extra monitor next to the tablets and smartphones that we give our children to keep them busy all the while we stare at the phones. We spend time in the subway scrolling through Facebook, Instagram, and Tick Tock as we check the time in our iPhone watches. Our attention has become more divided and media scientists have used screens to enrapture our attention. Ads display in the videos we watch, the vehicles we ride to work, the TV shows we watch, the music we listen to, and the websites we visit. Facebook, Instagram, and Tik Tok are the majority of sites people spend their time on these days. These sites are laden with thousands of ads that tell us one thing–-to shop. Leonard says that humans in big metropolitan cities do two things in their leisure time: watch TV (be online) and shop. According to an article by Ella Koeve and Nathaniel Pepper published in the New York Times Americans, “stuck at home during the coronavirus pandemic, with movie theaters closed and no restaurants to dine in, [h]ave been spending more of their lives online.” We are more connected than ever and because of that, we are more vulnerable to being targeted by media campaigns and advertisements that again tell us that our lives are horrible and that we can fix our lives if we only get out of the house to shop. It is a vicious cycle where we are essentially cogs that power the economic machine-–we are trapped in this infinite treadmill of watching ads on our screen which leads us to shop; then after work, watch TV and then shop again and so on. “Each of us in the U.S. is targeted with more than 3,000 advertisements a day. We each see more advertisements in one year than people 50 years ago saw in a lifetime. And if you think about it, what is the point of an ad except to make us unhappy with what we have. So, 3,000 times a day, we’re told that our hair is wrong, our skin is wrong, clothes are wrong, our furniture is wrong, our cars are wrong, we are wrong but that it can all be made right if we just go shopping” (Louis Fox, 2007). The scary part is that this behavior is mostly unconscious since we are technically programmed by advertisers to behave this way thereby developing a chronic shopaholic habit. Bees on the other hand perform that cyclical work of collecting nectar and transforming it into honey but their means of production keeps the ecosystem healthy while the things we buy are thrown away eventually. “At this rate of consumption, [stuff] can’t fit into our houses even though the average U.S. house size has doubled in this country since the 1970s” (Louis Fox, 2007). Well of course all goes out in the garbage. And that brings us to “disposal”, the last stop in the consumer’s economy. “This is the part of the materials economy we all know the most [Leonard says] because we have to haul the junk out to the curb ourselves” (Louis Fox, 2007). Astonishingly, “each of us in the United States makes 4 1/2 pounds of garbage a day. That is twice what we each made thirty years ago” (Louis Fox, 2007). Each of us holds a responsibility here because each of us buys a lot of stuff. “All of this garbage [stuff we bought] either gets dumped in a landfill, which is just a big hole in the ground, or if you’re really unlucky, first it’s burned in an incinerator and then dumped in a landfill” (Louis Fox, 2007). All that garbages and inclination is what “pollute[s] the air, land, water and, don’t forget, change[s] the climate” (Louis Fox, 2007). We humans have one of the biggest responsibilities in the world at the moment. This system is quite complex and has, as a successful investor and author Ray Dalio would say, cause-effect relationships that govern and dictate our lives. This system is detrimental to both ourselves and the world because in this system, as Leonard would suggest, people do not have value. The purpose of revealing and unveiling the specific mechanics of this market machinery and its evils is because we must point out the fact that the people that are most vulnerable are those of low-income communities all around our country. This unfortunate fact was made even more paramount during the rise of the Covid-19 pandemic which devastated populations of low income. High unemployment rate, lack of health insurance, and saving funds left many people even worse than before. This lack of resources has grown even more exponentially as we move ever more to a digital world with the rise of digital superpowers that will take hold of the consumer world in the time ahead.

Approaches to Sustainability

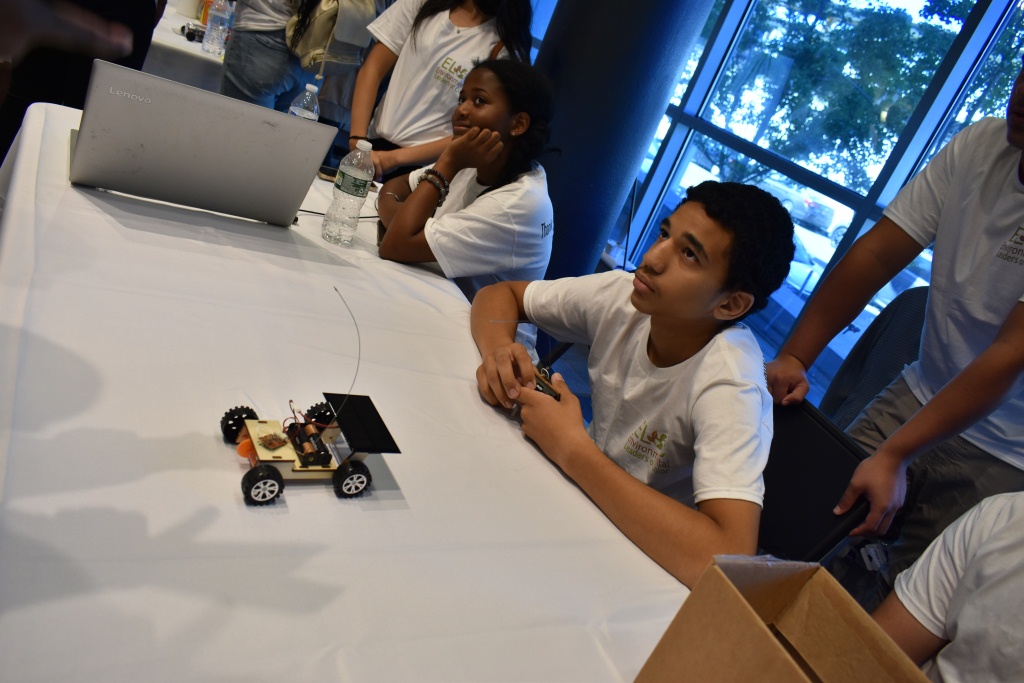

For Diana, founder of Environmental Leaders of Color (ELOC), her purpose for creating this initiative was to “keep in mind the struggles of people who do not have easy access to resources. People of color, people with reduced income, people who are homeless and who have a mental illness, people who are disabled, people who are elderly–the people who are the most vulnerable in our communities to reach out to them and identify the restrictions that prevent them from having access to [the help they need]. I thought deeply about the concept of what wealth is.” We have seen the power of massive advertisement from companies that constantly indoctrinates us that wealth is about acquiring material possessions-–nice expensive cars, smartphones, brand new clothes, etc. People have lost the utilitarian view of commodities and now view commodities as possessions that can be used for display.

We are caught up in impressions, in the approval of those who are also trapped in this cycle of possessions. We are caught up in superficiality. ELOC wants to push us to think deeply and ask questions regarding meaning and wealth. Wealth is having the assurance that if we need something, whether that is health insurance, being able to survive an illness, or if we lose our job, and even if we lose a lot we can survive. That is wealth. The question is we acquire things because we want to be identified as being part of a certain faction and a certain group. We are falling into the construction that advertisement has created for us. Someone has led us to go a different path. The idea that needs are different than wants is a very important one because that idea allows for the possibility of thinking twice about buying something. By simply asking “Is this a need or a want?” We can take a second look at the stuff we are buying and possibly stop ourselves from buying something that we don’t really need to buy at the moment. By living with that principle in mind, we can start becoming more mindful about our impulsive spending habits and understand that we can do more to help the world and other communities by learning to take control of ourselves.

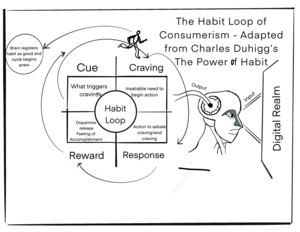

Interruption here becomes a very important idea and one where we all must make sure that we have a system in which we realize the way in which big corporations influence us to keep buying things and spend money we don’t have to impress people we don’t like. Here I must introduce a new human. One that is essentially thought up by the ELOC ETHOS and seeks to empower one thing only: the self and the world. The way to truly be free of a harmful habit loop, Duhigg argues, is by interrupting the cycle. When we get the cue and feel a desire to start the cycle we can instead go for a walk, call a friend or do some exercise and then let time pass. Interruption is key because by learning how to identify the habit we have to know its components. A habit is usually broken down into a cue followed by a craving. The craving makes us respond to the craving to satiate it with an action (i.e., eat the chocolate, smoke that cigarette, drink that 5th beer) and finally to a reward (dopamine release that comes with having performed the action). Because the action causes such a great feeling, the brain then registers that as a habit so that next time you can do it unconsciously (the brain works better when it doesn’t have to do too much thinking about what to drink in the morning before work since that’s a waste of time so it just plays the same recorded action). In order to escape this loop and the treadmill, we have to really take a deep look at ourselves and learn how to disrupt and abandon old habits and adopt new better ones for ourselves, for our communities, and for our planet. I will leave you with this: I once encountered a cartoon of another planet dressed as a doctor telling the planet Earth to brace herself for the news. As she stares in horror awaiting the news, the doctor planet tells her that he is sorry to inform her that she has humans. Now to be identified by a cartoonist as the human organism causing the plane to be deceased is plainly sad, to say the least. We do harm to our planet in terrifying ways and must think about ways to stop being a virus to her and instead become the antibodies that will fight and protect her and save her life. It is on us, the choice is our to be her virus or her cure.